I had the opportunity to visit the museum as part of a hosted trip provided by St Landry Parish tourism.

You might have never heard about the orphan trains in the United States, but the Orphan Train Museum in Opelousas Louisiana is keeping the history alive. The museum tells the story of those that arrived in Louisiana on the orphan trains and since opening has sought out the families of those that arrived to hear their stories.

Book your hotel in Opelousas

To understand this period in history you need to understand what was happening in the United States. Immigrants arriving in the United States mostly arrived by ship from Europe, and New York City was the port of choice for those entering the country. By the 1850’s there was a crisis in New York due to overcrowding, and no welfare assistance. Children whose parents had died or abandoned them were living on the streets as well as mothers who left their children at orphanages hoping they could take better care of them. Some estimates put homeless children at 30,000 in New York city, with many doing anything they could to survive. Sometimes that meant joining gangs where they would get arrested and placed in jail with adults.

Enter Charles Loring Brace, a minister who saw it as his duty to help the poor, living on the streets. In 1853 he established the Children’s Aid Society, and he believed that a child was better off with a family than living in an orphanage or the streets so he began the orphan train movement. In 1869 the New York Foundling Hospital was started by Sister Mary Irene Fitzgibbon of the Sisters of Charity of New York as a shelter for abandoned children. From 1854 to 1929 the Children’s Aid Society along with the New York Foundling Hospital, sent children on trains to almost every state as well as Canada and Mexico to be fostered by families. The main intention was to get farm and ranch families to take in and foster these children because they could always use the extra work hands around the farm. Families had to sign a contract regarding the treatment of the children. The younger children were to be cared for and schooled while the older children would work on the family farm in exchange for being cared for and given a home.

The children were put on trains with chaperones and would make stops at designated areas where people would choose a child. If no one chose the child, they would be returned to New York and take another train later. In some cases, families could request a child and even specify the gender, age, eye color and hair color. Since New York’s Foundling Hospital was run by Catholic nuns, the thought that Opelousas Louisiana would make for a good Orphan Train Depot since the area was predominantly Catholic. As a result, around 2,000 children from the Orphan Trains wound up in the area, where Rev. John Engberink of St. Landry Catholic Church was able to find families to foster the children.

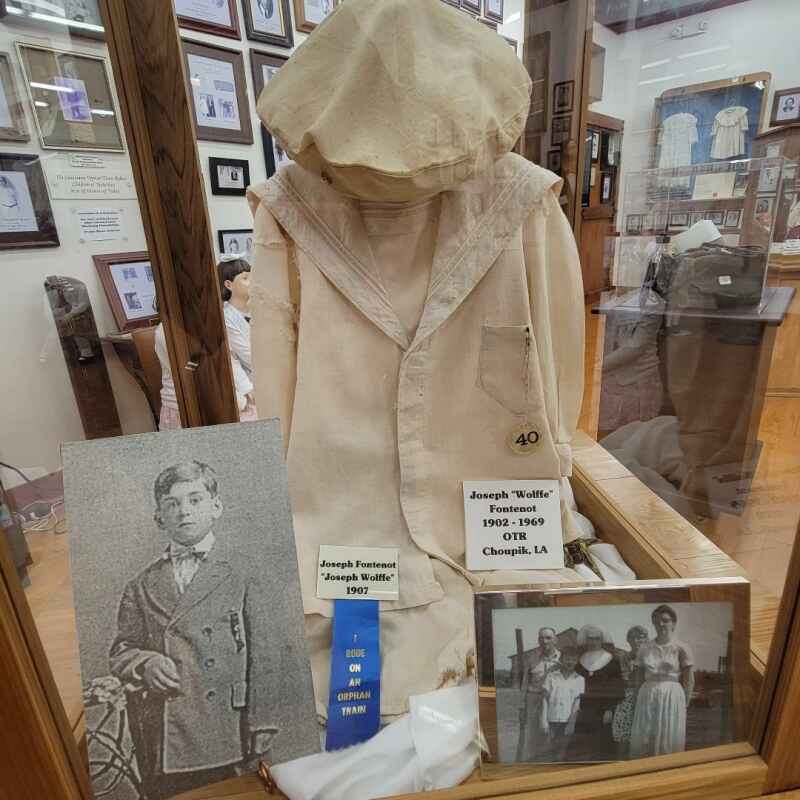

Opelousas Louisiana and the surrounding area was occupied by Cajuns, French speaking people originally from Canada. The children arriving on the trains spoke English, so right off the bat there were communication problems. The children arrived wearing a tag with their name on it and while some kept their name, many others took the last name of the family that raised them.

The children that were placed in the foster homes were checked on once a year to ensure they were not being mistreated. If there were problems, the children were taken out the home and returned to New York. A survey around 1910 showed 87% of the children had done well, while 8% had returned to New York and 5% had either died, disappeared or been arrested.

The Orphan Train Museum in Opelousas Louisiana opened in Oct 2009 by some of the descendants of the original Orphan Train children. Since that time, they have strived to get in touch with as many descendants of the children as possible in order to tell their stories.

The museum has a lot of original documents as well as photos of the children. They have helped descendants get records from New York, when possible, to find out about where their families originated. During the time of the orphan trains people did not discuss fostering or adopting children the way they do today. Many of the children took the last names of the fostering family and never discussed their earlier history. Some never told their wives or children after they grew into adulthood and their descendants only found out when they died.

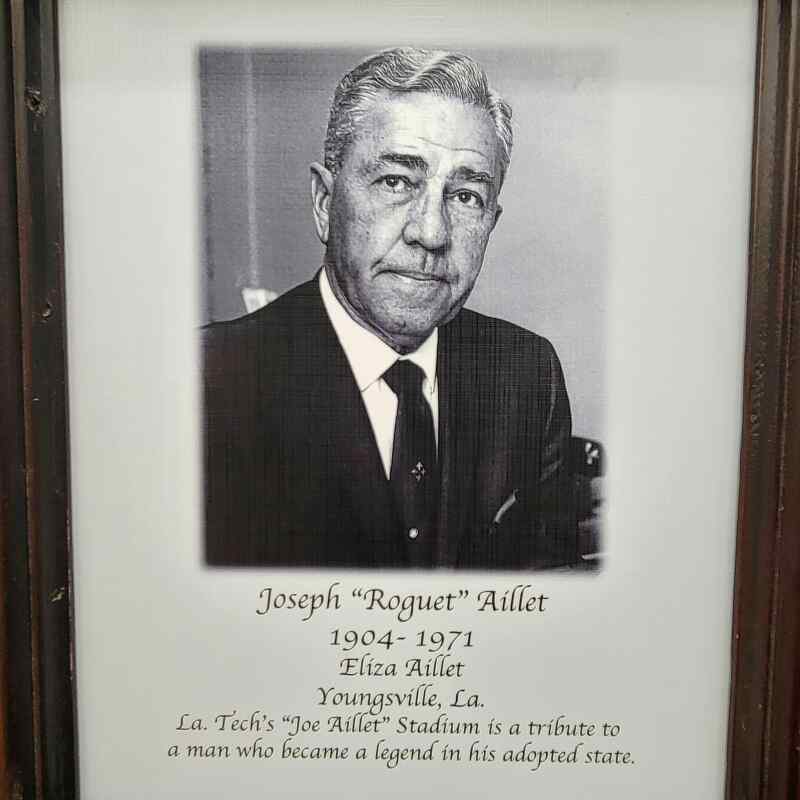

One such child was Joseph Fuourka, who arrived in Youngsville Louisiana, near Lafayette, in 1909 and was taken in by Johanni Roguet, the priest at St. Ann’s Catholic Church. Since a priest could not adopt a child, he gave the day to day duties of raising the young child to a widow named Eliza Aillet and his name was changed to Joseph Roguet Aillet. Young Joe excelled in school and later attended the University, ultimately becoming a football coach. In 1940 Joe Aillet became the head coach of Louisiana Tech where he remained until 1966.

Coach Aillet helped form the Gulf States conference and his team won 8 of the first 12 championships. He finished his career with 152 wins, 85 losses and 8 ties. The stadium at Louisiana Tech is named in his honor and he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame, as well as having a scholarship named after him. It wasn’t until just before he died that he revealed he was one of the Orphan Train children.

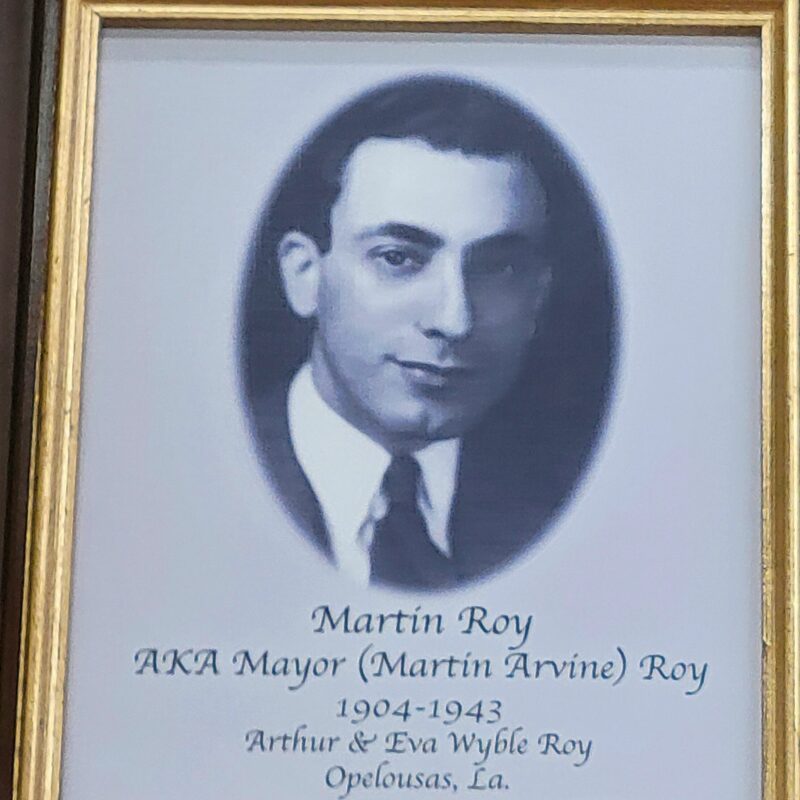

Another one of the children was Martin Arvine who arrived in Opelousas in 1907 at the age of 3. Martin was taken in by the Roy family and his named changed to Martin Arvine Roy. Although arriving a frightened child who did not speak the language, Martin eventually adapted and thrived with his new family. In 1936 he opened Roy Motors, a car dealership in Opelousas, that is still in business today and run by his descendants. In 1942 Martin Roy was elected Mayor of Opelousas Louisiana. Roy was also active in the Knights of Columbus, Kiwanis Club, Woodman of the World and the Opelousas Volunteer Fire Company.

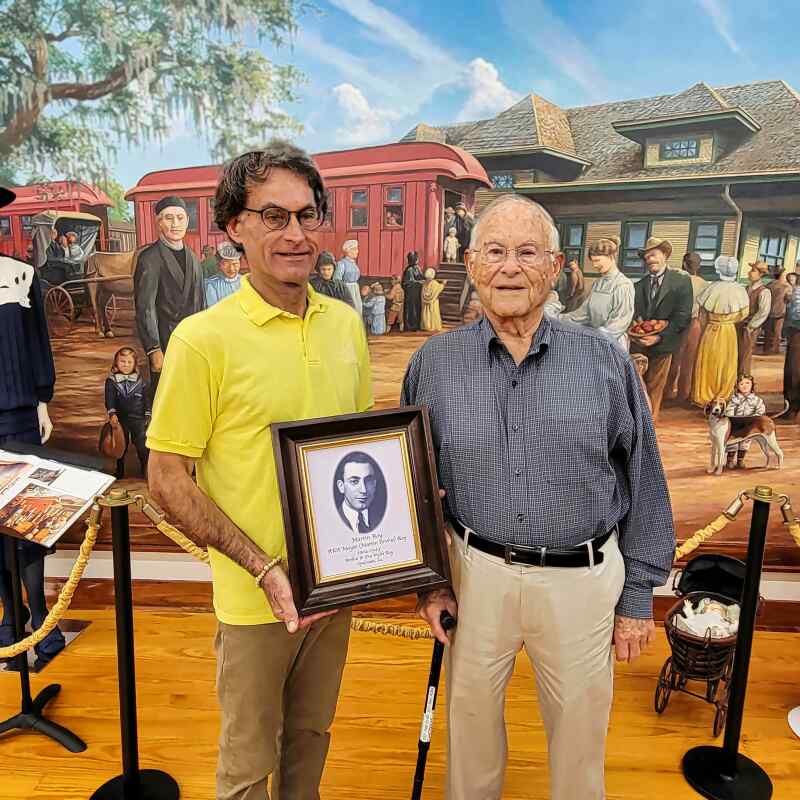

While only in office for one year, he tragically died in a boating accident in 1943. Although only serving for one year he had a huge impact. People from all over the State attended his funeral and all Opelousas businesses closed for his funeral. At first, his widow ran Roy Motors and eventually his son Martin Roy Jr. took over the business and it is still run by the family. His grandson, Charles Roy, is a board member of the Orphan Train Museum.

In the 1920’s the Orphan Trains became fewer as states began enacting laws that prohibited placing children across state lines. In 1912 President William Howard Taft signed into law the US Children’s Bureau Bill, which helped states support children and families, making the United States the first country to have a federal agency focused solely on children. By 1929 Orphan Trains were no longer needed. The organizations that had sent the children initially were still involved in helping families adopt children, but families would have to not only apply, but actually go to New York to adopt a child. As a result, not many rural farm families had that ability.

The majority of children that rode the Orphan Trains were not adopted but indentured, since they had been given to the charity by their families because they could not care for them. They worked on the family farms and were given schooling and room and board. They were checked on yearly by the organization that had sent them to ensure they were treated well and upon reaching the age of maturity returned to their original families in New York or left to go out on their own.

These are just a couple of the stories about the children of the Orphan Trains. There are many more you can find out about at the museum. The Orphan Train Museum keeps the stories of these children alive, and they live on through their accomplishments and their descendants.

The Orphan Train Museum is located at 223 South Academy Street in the historic Le Vieux Village in Opelousas Louisiana.

The hours are:

Tue – Fri 10am to 3pm

Saturday 10am to 2pm

Closed Sunday, Monday and Holidays

Admission:

Adults $5.00

Children, Seniors and Tours $3.00 per person

Recommended Articles

great article about my grandfather and my name sake

Martin A Roy III

also enjoy cigars

Thank you

Very Emotional And Endearing Stories. God Bless your Family’s Namesake. My Family bought many vehicles from Roy Motors. Wonderful People!